World Magazine

November, 2019

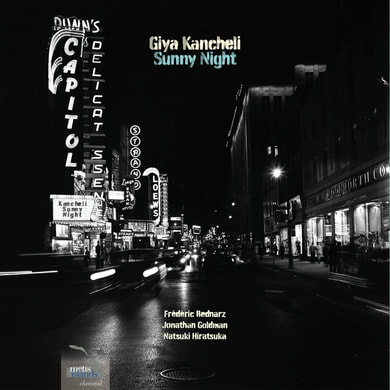

Shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, critics began singling out the compositions of the Georgia-born composer Giya Kancheli as prime examples of the musical riches that the Iron Curtain had been keeping from the free world. “Now comes a man,” wrote Michael Walsh in Time magazine, “who may well be the most important composer to emerge from the old Soviet Union since Dmitri Shostakovich.” Kancheli, 59 at the time (and, according to Walsh, a “devout Orthodox Christian”), would still have a quarter century to go.Kancheli died in October. And, ironically, given his reputation for large-scale compositions characterized by only partially resolved internal conflicts, the latest recordings of his works focus on his sweet, nostalgic violin-and-piano miniatures: Mariya Nesterovska and Nenad Lečić’s 18 Miniatures for Violin and Piano (Cioccapri) and Frédéric Bednarz, Jonathan Goldman, and Natsuki Hiratsuka’s Sunny Night (Metis Island). Their considerable overlap notwithstanding, they complement each other and eulogize Kancheli simultaneously. —A.O.

ClassicsToday, review by David Vernier (USA)

Artistic Quality: 10 Sound Quality: 10

You’re in a café, a quiet little out of the way place. The sudden sound of violin and piano, perhaps later a bandonéon, playing a sweet, romantic tune creates the perfect atmosphere for evening romance, contemplation, or just enjoying the wine and the solitude (sound clips). This is not the sort of music you might expect from Georgian composer Giya Kancheli, who most listeners know for his symphonic works or more “serious” chamber pieces, but then, most listeners probably are not aware of Kancheli’s extensive contributions as a composer of music for theatrical plays and film. Nor might they be familiar with his several dozen arrangements—”miniatures” for violin and piano, or for solo piano—of selections from that repertoire, which provided the material for this recording.

We hear pieces from plays and films such as Hamlet, Don Quixote, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, King Lear, Waiting for Godot (En attendant Godot), The Caucasian Chalk Circle, and The Eccentrics. The mood, generally, is mellow, wistful, dreamy, with a sometimes pop-style/jazzy edge à la Michel Legrand or Francis Lai. But then, the mood can quickly change, as it does with the pounding piano chords announcing a theme from the film Kin-dza-dza! (sound clip), for which I cannot resist a description: Kin-dza-dza! is a “1986 Soviet-Russian-Georgian sci-fi dystopian tragicomedy cult film,” heralded by more than one critic as perhaps the best science fiction film you’ve never heard of. The story involves a couple of Muscovites (one of whom is a violinist) who get transported to the planet Pluke in the galaxy of the title. It’s certainly not Shakespeare, nor Beckett, but it does make you curious, no? (Not to get too carried away, here, but you can actually watch it online.)

There are a few other mood-shifting moments, including an alternately playfully sensuous and raunchy piece for bandonéon, violin, and piano titled Instead of a Tango, but this is a well-crafted program that invites us into an intimate atmosphere of character and emotion, of beautiful melody sung by violin in its purest, sweetest voice and piano both assertive and seductive. Definitely an unusual disc, but this trio—Frédéric Bednarz (violin), Natsuki Hiratsuka (piano), and Jonathan Goldman (bandonéon)—not only had the right idea in putting this together, but they may have created a demand for more. (Hint, hint.)

Heavenly Violin and Piano Music by Giya Kancheli , review by Allan J. Cronin, New Music Buff (USA)

For this reviewer, my relationship with the music of Giya Kancheli (1935- ) began with the symphonies (I think there’s seven now) with the character of some outrageous dynamic contrasts such that they spawned warning levels on the package containing the CD. It was only after that, when ECM began to release the “holy minimalist” type works, that I first heard those.

Now comes Canadian violinist Frederic Bednarz who, along with pianist Natsuki Hiratsuka and bandoneon player Jonathan Goldman have recorded some incredibly lovely chamber music which has not been previously released or widely distributed.

Well its hard to say why these have not been widely heard because they are just beautiful. These are miniatures, all clock in at less than 4 minutes but all have a certain charm that relies neither on the dynamic range or the “holy minimalist” meme. These are simply delightful neo-romantic pieces that could not fail to charm a recital audience. Bednarz clearly knows and loves these little gems. His playing is both sincere and, I think, definitive. In this album he shows this lesser known aspect of the composer’s work. Certainly there have been releases of Kancheli’s chamber orchestra pieces and a string quartet but this is the first recording this reviewer has heard of the violin and piano (and bandoneon) music.

Doubtless there are musical and musicological aspects to this music which escape the average listener (this one included) so no attempt will be made here to analyze these works. Bednarz provides concise but useful liner notes in the gatefold cover to the CD.

Once again our neighbors to the north have scaled the metaphorical art barrier between our adjacent countries to bring this delightful music to light. It is a welcome addition to the Kancheli discography and a delight in your CD player. Whether as calm background or for intense listening this disc is a gem.

N.B. As of this writing the physical disc does not appear to be available from Amazon but it is available through the usual streaming services. If you can get the physical disc it is worth it for the notes though.

Ici Musique . Radio-Canada, Frédéric Cardin

La musique du compositeur géorgien Giya Kancheli est l’une des plus originales et émotionnellement séduisantes d’aujourd’hui. Le violoniste Frédéric Bednarz et la pianiste Natsuki Hiratsuka, avec le bandonéoniste Jonathan Goldman à l’occasion, proposent l’album Sunny Night, une porte d’entrée toute simple sur l’univers du compositeur. Trop simple? Je vous en parle. Sunny Night est un recueil de petites pièces pour violon et piano, avec bandonéon ici et là, extraites de musiques que Kancheli a écrites pour le cinéma et le théâtre. Atmosphère mélancolique, mélodies agréables, écriture épurée, mais imprégnée d’une touchante tendresse, Sunny Night a quelque chose des albums de nouvelle musique classique très accessible qui se multiplient ces jours-ci. Entre Andréa Stréliski et Chilly Gonzales (approximativement), et s’accompagnant de quelques réminiscences de musiques pour Fellini ou Wajda, Sunny Night est d’une écoute franchement agréable, sans complications inutiles.

Les Montréalais Bednarz, Hiratsuka et Goldman font preuve d’une forte connivence, et dessinent quelque chose comme des courts métrages agréablement vieillots, un peu noir et blanc, un peu sépia, avec ces nuits étrangement éclairées et lumineuses. Sunny Night, le titre d’un film oui, mais le symbole idéal de cette musique. On se surprend à voir des paysans et des villages isolés dans leCaucase, comme figés dans le temps, presque oubliés du monde moderne et filmés par un cinéaste nostalgique d’un monde qui refuse de mourir. Les films et les pièces pour lesquelles Kancheli a écrit ces musiques n’ont peut-être rien à voir avec cela, mais l’âme du Géorgien est tellement imprégnée par ses racines culturelles que sa musique en reste marquée, peu importe le sujet qu’elle aborde.

Tout cela est assez réussi. Cela dit, comme je le mentionnais plus haut, la musique de concert de Kancheli est l’une des plus intéressantes de notre époque. Elle est plus complexe que cette musique de scène, certes fort belle et magnifiquement interprétée, mais elle est tout aussi accessible et surtout encore plus bouleversante. Sa puissance émotionnelle et dramatique est impressionnante. Si vous aimez Sunny Night, votre prochain rendez-vous avec Kancheliest tout indiqué : des chefs-d’œuvre comme Morning Prayers, Abii ne Viderem ou Exil vous attendent. Cherchez ces titres dans Google (il faut bien que ça serve à quelque chose d’utile parfois!), et vous m’en donnerez des nouvelles. En attendant, Sunny Night vous bercera doucement.

"Album of the Week" CBC radio "In Concert" April 28, 2019

"This week is the dreamy and hopeful music by the Georgian composer Giya Kancheli..music that lets little light into the world..It's a wonderful new recording and this week "In Concert" record of the week..by the wonderful duo of Bednarz and Hiratsuka." Paolo Pietropaolo

The Listener's Club, Timothy Judd

Radio-Canada, Medium Large, Frédéric Lambert, Mars, 2019

The WholeNote, Toronto, review by Andrew Timar

I get particular satisfaction from listening to an album rendered stylishly by gifted Canadian musicians. A good example is Sunny Night, a collection of 17 miniatures originally scored for the cinema and theatre by Giya Kancheli (b.1935) recorded at McGill University in Montreal by the duo of Frédéric Bednarz (violin) and Natsuki Hiratsuka (piano).

The well-known Georgian composer Kancheli, currently living in Belgium, is an unabashed romantic when it comes to composing music. “Music, like life itself, is inconceivable without romanticism. Romanticism is a high dream of the past, present, and future – a force of invincible beauty which towers above, and conquers the forces of ignorance, bigotry, violence and evil,” states Kancheli in the liner notes.

The highlights on Sunny Night are the two works for violin, piano and bandoneon (Jonathan Goldman), an instrument closely associated with the tango. Earth, This Is Your Son for the trio is episodic and dramatic, dominated by minor key tonalities. At just over five minutes it is also the most substantial work on the album. It’s more a concert piece than incidental music.

Not only unapologetically melody-driven, romantic and tonal – often gently drawing on early 20th-century vernacular genres such as the tango – the musical language on Sunny Night also seeks to capture a single mood befitting the music’s original theatrical function. In that it succeeds admirably, though sometimes the effect verges on overt sentiment. There are times however when that is just what’s needed.

November, 2019

Shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, critics began singling out the compositions of the Georgia-born composer Giya Kancheli as prime examples of the musical riches that the Iron Curtain had been keeping from the free world. “Now comes a man,” wrote Michael Walsh in Time magazine, “who may well be the most important composer to emerge from the old Soviet Union since Dmitri Shostakovich.” Kancheli, 59 at the time (and, according to Walsh, a “devout Orthodox Christian”), would still have a quarter century to go.Kancheli died in October. And, ironically, given his reputation for large-scale compositions characterized by only partially resolved internal conflicts, the latest recordings of his works focus on his sweet, nostalgic violin-and-piano miniatures: Mariya Nesterovska and Nenad Lečić’s 18 Miniatures for Violin and Piano (Cioccapri) and Frédéric Bednarz, Jonathan Goldman, and Natsuki Hiratsuka’s Sunny Night (Metis Island). Their considerable overlap notwithstanding, they complement each other and eulogize Kancheli simultaneously. —A.O.

ClassicsToday, review by David Vernier (USA)

Artistic Quality: 10 Sound Quality: 10

You’re in a café, a quiet little out of the way place. The sudden sound of violin and piano, perhaps later a bandonéon, playing a sweet, romantic tune creates the perfect atmosphere for evening romance, contemplation, or just enjoying the wine and the solitude (sound clips). This is not the sort of music you might expect from Georgian composer Giya Kancheli, who most listeners know for his symphonic works or more “serious” chamber pieces, but then, most listeners probably are not aware of Kancheli’s extensive contributions as a composer of music for theatrical plays and film. Nor might they be familiar with his several dozen arrangements—”miniatures” for violin and piano, or for solo piano—of selections from that repertoire, which provided the material for this recording.

We hear pieces from plays and films such as Hamlet, Don Quixote, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, King Lear, Waiting for Godot (En attendant Godot), The Caucasian Chalk Circle, and The Eccentrics. The mood, generally, is mellow, wistful, dreamy, with a sometimes pop-style/jazzy edge à la Michel Legrand or Francis Lai. But then, the mood can quickly change, as it does with the pounding piano chords announcing a theme from the film Kin-dza-dza! (sound clip), for which I cannot resist a description: Kin-dza-dza! is a “1986 Soviet-Russian-Georgian sci-fi dystopian tragicomedy cult film,” heralded by more than one critic as perhaps the best science fiction film you’ve never heard of. The story involves a couple of Muscovites (one of whom is a violinist) who get transported to the planet Pluke in the galaxy of the title. It’s certainly not Shakespeare, nor Beckett, but it does make you curious, no? (Not to get too carried away, here, but you can actually watch it online.)

There are a few other mood-shifting moments, including an alternately playfully sensuous and raunchy piece for bandonéon, violin, and piano titled Instead of a Tango, but this is a well-crafted program that invites us into an intimate atmosphere of character and emotion, of beautiful melody sung by violin in its purest, sweetest voice and piano both assertive and seductive. Definitely an unusual disc, but this trio—Frédéric Bednarz (violin), Natsuki Hiratsuka (piano), and Jonathan Goldman (bandonéon)—not only had the right idea in putting this together, but they may have created a demand for more. (Hint, hint.)

Heavenly Violin and Piano Music by Giya Kancheli , review by Allan J. Cronin, New Music Buff (USA)

For this reviewer, my relationship with the music of Giya Kancheli (1935- ) began with the symphonies (I think there’s seven now) with the character of some outrageous dynamic contrasts such that they spawned warning levels on the package containing the CD. It was only after that, when ECM began to release the “holy minimalist” type works, that I first heard those.

Now comes Canadian violinist Frederic Bednarz who, along with pianist Natsuki Hiratsuka and bandoneon player Jonathan Goldman have recorded some incredibly lovely chamber music which has not been previously released or widely distributed.

Well its hard to say why these have not been widely heard because they are just beautiful. These are miniatures, all clock in at less than 4 minutes but all have a certain charm that relies neither on the dynamic range or the “holy minimalist” meme. These are simply delightful neo-romantic pieces that could not fail to charm a recital audience. Bednarz clearly knows and loves these little gems. His playing is both sincere and, I think, definitive. In this album he shows this lesser known aspect of the composer’s work. Certainly there have been releases of Kancheli’s chamber orchestra pieces and a string quartet but this is the first recording this reviewer has heard of the violin and piano (and bandoneon) music.

Doubtless there are musical and musicological aspects to this music which escape the average listener (this one included) so no attempt will be made here to analyze these works. Bednarz provides concise but useful liner notes in the gatefold cover to the CD.

Once again our neighbors to the north have scaled the metaphorical art barrier between our adjacent countries to bring this delightful music to light. It is a welcome addition to the Kancheli discography and a delight in your CD player. Whether as calm background or for intense listening this disc is a gem.

N.B. As of this writing the physical disc does not appear to be available from Amazon but it is available through the usual streaming services. If you can get the physical disc it is worth it for the notes though.

Ici Musique . Radio-Canada, Frédéric Cardin

La musique du compositeur géorgien Giya Kancheli est l’une des plus originales et émotionnellement séduisantes d’aujourd’hui. Le violoniste Frédéric Bednarz et la pianiste Natsuki Hiratsuka, avec le bandonéoniste Jonathan Goldman à l’occasion, proposent l’album Sunny Night, une porte d’entrée toute simple sur l’univers du compositeur. Trop simple? Je vous en parle. Sunny Night est un recueil de petites pièces pour violon et piano, avec bandonéon ici et là, extraites de musiques que Kancheli a écrites pour le cinéma et le théâtre. Atmosphère mélancolique, mélodies agréables, écriture épurée, mais imprégnée d’une touchante tendresse, Sunny Night a quelque chose des albums de nouvelle musique classique très accessible qui se multiplient ces jours-ci. Entre Andréa Stréliski et Chilly Gonzales (approximativement), et s’accompagnant de quelques réminiscences de musiques pour Fellini ou Wajda, Sunny Night est d’une écoute franchement agréable, sans complications inutiles.

Les Montréalais Bednarz, Hiratsuka et Goldman font preuve d’une forte connivence, et dessinent quelque chose comme des courts métrages agréablement vieillots, un peu noir et blanc, un peu sépia, avec ces nuits étrangement éclairées et lumineuses. Sunny Night, le titre d’un film oui, mais le symbole idéal de cette musique. On se surprend à voir des paysans et des villages isolés dans leCaucase, comme figés dans le temps, presque oubliés du monde moderne et filmés par un cinéaste nostalgique d’un monde qui refuse de mourir. Les films et les pièces pour lesquelles Kancheli a écrit ces musiques n’ont peut-être rien à voir avec cela, mais l’âme du Géorgien est tellement imprégnée par ses racines culturelles que sa musique en reste marquée, peu importe le sujet qu’elle aborde.

Tout cela est assez réussi. Cela dit, comme je le mentionnais plus haut, la musique de concert de Kancheli est l’une des plus intéressantes de notre époque. Elle est plus complexe que cette musique de scène, certes fort belle et magnifiquement interprétée, mais elle est tout aussi accessible et surtout encore plus bouleversante. Sa puissance émotionnelle et dramatique est impressionnante. Si vous aimez Sunny Night, votre prochain rendez-vous avec Kancheliest tout indiqué : des chefs-d’œuvre comme Morning Prayers, Abii ne Viderem ou Exil vous attendent. Cherchez ces titres dans Google (il faut bien que ça serve à quelque chose d’utile parfois!), et vous m’en donnerez des nouvelles. En attendant, Sunny Night vous bercera doucement.

"Album of the Week" CBC radio "In Concert" April 28, 2019

"This week is the dreamy and hopeful music by the Georgian composer Giya Kancheli..music that lets little light into the world..It's a wonderful new recording and this week "In Concert" record of the week..by the wonderful duo of Bednarz and Hiratsuka." Paolo Pietropaolo

The Listener's Club, Timothy Judd

Radio-Canada, Medium Large, Frédéric Lambert, Mars, 2019

The WholeNote, Toronto, review by Andrew Timar

I get particular satisfaction from listening to an album rendered stylishly by gifted Canadian musicians. A good example is Sunny Night, a collection of 17 miniatures originally scored for the cinema and theatre by Giya Kancheli (b.1935) recorded at McGill University in Montreal by the duo of Frédéric Bednarz (violin) and Natsuki Hiratsuka (piano).

The well-known Georgian composer Kancheli, currently living in Belgium, is an unabashed romantic when it comes to composing music. “Music, like life itself, is inconceivable without romanticism. Romanticism is a high dream of the past, present, and future – a force of invincible beauty which towers above, and conquers the forces of ignorance, bigotry, violence and evil,” states Kancheli in the liner notes.

The highlights on Sunny Night are the two works for violin, piano and bandoneon (Jonathan Goldman), an instrument closely associated with the tango. Earth, This Is Your Son for the trio is episodic and dramatic, dominated by minor key tonalities. At just over five minutes it is also the most substantial work on the album. It’s more a concert piece than incidental music.

Not only unapologetically melody-driven, romantic and tonal – often gently drawing on early 20th-century vernacular genres such as the tango – the musical language on Sunny Night also seeks to capture a single mood befitting the music’s original theatrical function. In that it succeeds admirably, though sometimes the effect verges on overt sentiment. There are times however when that is just what’s needed.

Lekeu | Franck | Boulanger

Natsuki Hiratsuka, piano

Natsuki Hiratsuka, piano

|

Album reviews Frédéric Bednarz and Natsuki Hiratsuka bring exceptionally fine, idiomatic and subtle performances of works for violin and piano by Guillaume Lekeu, César Franck and Lili Boulanger on a release from metis islands music. (read the full review) The Classical Reviewer, Bruce Reader ★★★★ Bednarz and Hiratsuka capture the post-Wagnerian sound world of Lekeu with a Gallic sensitivity, which also proves ideal in the Nocturne, but slightly over-discreet for Franck’s boldest climaxes. Julian Haylock, BBC Music Magazine ★★★★★★ Les chambristes Frédéric Bednarz au violon et Natsuki Hiratsuka au piano ont concocté un album des plus divins! Le programme tout français regroupe deux sonates majeures du répertoire, celles de Lekeu et de Franck, ainsi qu'un petit nocturne de Lili Boulanger et le tout est interprété avec une finesse et un sens musical exquis. De la sonate de Guillaume Lekeu, l'oeuvre la plus connue de ce compositeur un peu oublié, voire négligé, les musiciens proposent une interprétation fluide et mouvante. Le caractère est toujours juste, le phrasé respire l'intimité et la tendresse, et la parfaite complicité des musiciens transparaît dans les moindres détails de cette charmante partition. La sonate de César Franck est ici abordée avec une aisance dans la tension et de l'émotion, tout en conservant une belle maîtrise des tempos et l'équilibre des instruments. Le charmant Nocturne de Lili Boulanger qui clôt le disque résume à lui seul l'ensemble de l'entreprise : en tensions et rêveries, ces deux musiciens sensibles et intelligents livrent une musique maîtrisée avec un naturel et une élégance délectables. Un must pour les amateurs de musique de chambre. Eric Champagne, La Scena Musicale There’s another performance of the Franck Violin Sonata on a new CD featuring works by Lekeu, Franck and Boulanger from the Montreal violinist Frédéric Bednarz and pianist Natsuki Hiratsuka (Metis Islands Music MIM-0006). Guillaume Lekeu and Lili Boulanger (Nadia’s younger sister) both died at the tragically young age of 24. Lekeu’s Sonata in G Major is a fine three-movement work, with its long violin lines and agitated piano in the outer movements somewhat reminiscent of the Franck, which was written just six years earlier. Bednarz’s beautiful sweetness of tone is evident right from the start. Boulanger was always in fragile health, and her works often seem to display her awareness of her condition. Nocturne is a simply lovely and delightful piece, again perfectly suited to Bednarz’s sweet tone. The Franck Sonata is the centrepiece of the CD, and again it’s the tonal quality of the violin playing that makes the biggest impression. Hiratsuka gives perhaps a bit less weight to the piano part in the opening movement, and there seems to be less turbulence and urgency in the second movement than on the Ehnes/Armstrong CD, but this is still a strong, musical and highly enjoyable performance. Terry Robbins, The Wholenote Here is an interesting program which avoids the routine by pairing the over-familiar Franck violin sonata with the very much less often heard sonata by Guillaume Lekeu and the almost never heard Nocturne by Lili Boulanger. At least once told—perhaps twice—is the story of my first encounter with Lekeu’s sonata on a mid-1950s RCA LP, performed by Yehudi Menuhin and Marcel Gazelle. The piece struck me as a “wanderer’s fantasy” if ever there was one, as I kept an impatient eye on the turntable arm slowly making its way across the grooves and wondering, not when, but if it would ever end. Lekeu may have lived to be only 24 (1870–1894) and to have composed fewer than 30 works during his short lifespan, but not a few of them, including the violin sonata, lack nothing for length or ambition. I’ve since, of course, come to terms with Lekeu’s discursive style, which is characterized by a “restless chromaticism,” punctuated by the periodic upwelling of molten passion; and of late, his violin sonata seems to have emerged as his most representative work, with relatively recent recordings by Tasmin Little and Alina Ibragimova, to name just two. Lekeu was a student of César Franck, so Franck’s deservedly popular violin sonata—possibly his finest work—is a natural discmate for the Lekeu, but the Nocturne by Lili Boulanger adds an unusual touch to this program. Longer-lived than Lekeu by only one year, Lili Boulanger (1893–1918), who died at 25 of an intestinal disorder, was the younger and less famous sister of Nadia Boulanger, one of the most influential music educators and academicians of the 20th century. Sister Lili studied organ with Louis Vierne and may actually have inherited a more native talent for composition than did Nadia, but like Lekeu, she managed to leave fewer than three dozen works, most of which are short pieces for voice and piano or chorus and piano. Boulanger’s Nocturne on this disc is dated 1911 and was composed originally for flute and piano, in which form it was recorded by Susan Milan and reviewed by Richard Burke in 19:2; and in an arrangement for flute and orchestra, in which form it was recorded by James Galway and reviewed by John Ditsky in 07:3. The alternate version for violin and piano was recorded by both Janine Jensen and Arnold Steinhardt, reviewed respectively by Robert Maxham in 34:6 and by John Bauman in 09:5. It’s a slight piece, just over three minutes in duration and somewhat in the style of a French salon number of the period, but the piano’s strangely modernistic, off-kilter chords that accompany the none-too-rooted melody line, almost sound like they belong to a different piece. There’s something quirkily out of sync or out of sorts about this music that makes it strangely unsettling. Frédéric Bednarz and Natsuki Hiratsuka are both new to me, though I see that they recorded a disc of Szymanowski and Shostakovich for this same label, which was well received by Robert Maxham in 38:2. For the Franck sonata, of course, there is fierce competition, with many excellent versions to choose from. I will cite only two of my favorites, one of which is with Augustin Dumay and Maria João Pires on Deutsche Grammophon (not Dumay’s remake with Louis Lortie on Onyx), and the other one of which is with Vadim Repin and Nikolai Lugansky, also on Deutsche Grammophon. Bednarz and Hiratsuka take a somewhat different and actually refreshing approach to the piece, adopting slightly quicker tempos in all four movements and avoiding other players’ tendencies to exaggerate some of the score’s expressive excesses. Franck can never be accused of the sin of French aloofness and reserve; if anything, his music was criticized in its own time for being practically salacious in its super-heated sensuality. Bednarz downplays that aspect of the work with measured vibrato and tempered tone, while Hiratsuka keeps the line flowing. I don’t wish to convey the impression that this is a performance cleansed of emotion or passion; to the contrary, there’s a real sense of rapport between these players and Franck’s music. Rather, I’d describe the reading as one that restores a sense of Gallic balance and refinement to a work in which point-making is often inflated and italicized for dramatic effect. The Lekeu sonata, a piece which slowly grows on you, is also very well done. With this second Metis Islands release, Frédéric Bednarz and Natsuki Hiratsuka are well on their way to establishing themselves as a formidable violin and piano duo. Highly recommended. Jerry Dubins, Fanfare |

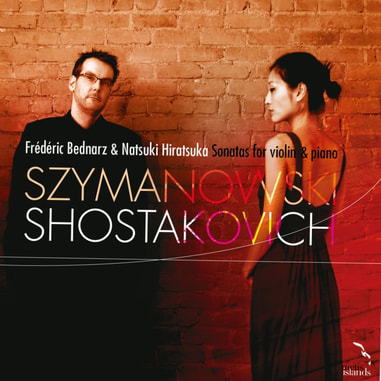

Szymanowski | Shostakovich

Natsuki Hiratsuka, piano

Natsuki Hiratsuka, piano

Album reviews

These works, from either end of their composers’ output, make for an unlikely yet effective pairing. Szymanowski’s Violin Sonata (1909) is often seen as a product of the period when he was still in thrall to German late-Romanticism, yet echoes of Fauré, Franck and Enescu make its ‘French’ provenance the more tangible. Frédéric Bednarz and Natsuki Hiratsuka bring flexibility to the rhetoric of its initial Allegro, then underline the plaintiveness of the Andantino as well as the resolve of the finale when it builds to its decisive close: the piece emerging as formally more cohesive and expressively less wayward than is often the case.

Where Szymanowski luxuriates, Shostakovich ruminates: the latter’s Violin Sonata (1968) has often seemed among the most forbidding of his later works and it is to these performers’ credit that the speculative dialogue of the opening Moderato feels not in the least arid or the confrontational exchanges of the central Allegretto not lacking in textural clarity. Nor does the final Largo lose focus as it heads to its eloquent climax before returning to those fugitive gestures with which the work had begun.

Those who prefer to invest in these works as part of single-composer discs could well turn to Alina Ibragimova for the Szymanowski and Isabelle Faust for the Shostakovich. If the present coupling appeals, however, it should be acquired with confidence.

Richard Whitehouse, Gramophone

The Montreal-born violinist Frédéric Bednarz is joined by his wife, pianist Natsuki Hiratsuka, in a CD of Sonatas for violin and piano by Szymanowski and Shostakovich (Metis Islands Music MIM-0004 metis-islands.com). Karol Szymanowski’s Sonata in D Minor, Op.9, is an early work from 1904; it’s a traditional late-Romantic piece with more than a passing reference to the Franck sonata, and is given a clear, thoughtful reading by both players. The Shostakovich Sonata Op.134 is, by contrast, a late work, written in 1968 for David Oistrakh’s 60th birthday; as with so much late Shostakovich, it never seems to shake that all-pervasive sense of nervous apprehension, desolation and loss of hope. Again, the playing is sensitive and clear, with a particularly effective Largo, the third and final movement which is almost as long as the first two movements put together. There could perhaps be a bit bigger emotional range in places – maybe more of a raw edge at times – but these are beautifully balanced and satisfying performances.

Terry Robbins, The WholeNote

★★★★★

Violinist Frédéric Bednarz has been a ubiquitous presence in Montreal’s chamber music community for many years. Now a member of the Molinari String Quartet, he has also begun of late to turn his attention to the violin and piano duo repertoire, aided and abetted by Natsuki Hiratsuka, a pianist of great skill and sensitivity. Together, they offer up mesmerizing performances of Dmitri Shostakovich’s great violin sonata, and the less well-known, but fascinating and beautiful late-romantic sonata by Karol Szymanowski. Bednarz has a warm, round, almost sweet sound, but he is not afraid to get his hands dirty. There are moments in the Shostakovich that are absolutely searing, all the more so because of the strength and intensity of Hiratsuka’s pianism, and the duo’s lockstep ensemble playing. The less familiar Op. 9 sonata by Szymanowski makes for a very pleasing pairing, with its late-romantic language evocative of Franck and to some extent, the impressionists – it is a work that simultaneously looks forward and backwards, inviting a certain amount of levity that very effectively balances out the tortured intensity of the Shostakovich. This is a disc worth having.

Pemi Paull, La Scena Musicale

Moving further east, young Montreal-born violinist Frédéric Bednarz and pianist Natsuki Hiratsuka make a strong impression in contrasting the late-Romantic style of early Szymanowski with the dark, sparse territory of late Shostakovich (Metis Islands MIM 0004). Comparing the disc’s first and last tracks emphasises the contrast. Szymanowski’s Allegro moderato has Romantic grandeur, which Bednarz conveys with flair. In Shostakovich’s slow, searching passacaglia finale, Bednarz maintains a sense of gravitas as well as enigma. Together with Hiratsuka, he creates a powerful atmosphere around this often arid soundscape. The second movement is a devil’s dance, here relatively unsneering but still effective, and technically assured. Bednarz brings a gorgeous tone to Szymanowski’s lyrical slow movement, the high-lying writing drawing sustained sweetness. In this movement and the next, Hiratsuka’s neat handling of the often dense texture is key. The disc’s trayless digipack presentation means that there are scant notes on the works or artists, but the recording itself is clear yet spacious. A highly recommended release from an instinctive musical partnership.

Edward Bhesania, The Strad, London.

Violinist Frédéric Bednarz and pianist Natsuki Hiratsuka open the first movement of Karol Szymanowski's early Violin Sonata with a commanding shot, and they maintain the level it sets as the movement proceeds. Bednarz proves himself capable of deploying a wide variety of violinistic effects, from the elusively shimmery to the soaringly declamatory. And that palette fits Szymanowski's work to perfection. Hiratsuka's a sympathetic partner, exploring in collaboration with him the composer's colorful harmonies and lush melodies. She evinces a special sensitivity to the haunting sonorities that open the second movement; the duo brings a fey magic to the pizzicato middle section and returns to the opening section with an eerie reminiscence of Frédéric Chopin. They communicate the agitated state of the finale's opening and rise to the emotional richness of the middle section. If Szymanowski's sonata hasn't yet penetrated the standard repertoire, Bednarz and Hiratsuka play it as though it should have.

Dmitri Shostakovich's Violin Sonata, another work that seems to hesitate outside the canon without entering, displays a spiritual affinity for Sergei Prokofiev's Violin Sonata in F Minor in the bleakness of its mood and in the bitter expostulations of its second movement. But Shostakovich's sonata raises these emotional states to a higher power of expression. What sounds merely gloomy in Prokofiev's work sounds desperate in Shostakovich's; what sounds eerie in Prokofiev's, terrifying in Shostakovich's. David Oistrakh, the work's dedicatee (what a birthday present!), didn't soften the brutal impact the piece could make. Bednarz does, creating with Hiratsuka a kinder and gentler profile that might make it more accessible to general audiences (the elegance of Bednarz's tone production perhaps makes that inevitable). But they haven't violated its tough core, as their reading of the second movement shows. The final movement, a passacaglia (the same general form as the one the composer employed in his First Violin Concerto, but with an entirely different effect, although this movement also includes some moments of great nobility and even warmth), sounds ominously elegiac though not ponderous, and unsettled though resigned, in the duo’s reading. In Fanfare 26:5, I noted that although Ilya Grubert's performance on Channel Classics 16398 conjured "a sonorous maelstrom in the Sonata's second movement" it failed to capture "both the last measure of Oistrakh's fervor and the caustic bite of his pessimism" (Mobile Fidelity 909) and in the Sonata's last movement, just didn't equal Oistrakh's "depth of reflection." Neither does the reading of Oistrakh's own student, Lydia Mordkovich on Chandos 8988. And these reviews haunt me as I consider Bednarz's and Hiratsuka's case. Yet in Fanfare 30:2, I recognized the validity of Leila Josefowicz's cogent yet very different realization of this dense and multifariously expressive work. How, then, do Bednarz and Hiratsuka measure up to this different standard? Bednarz sounds richer and loamier than does Josefowicz in the first movement, which he takes more than a minute slower (but the timing doesn't tell the whole tale); he does so as well in the slow movement, but in that case, extra bite and energy enliven Josefowicz's reading. The third movement differs in the two accounts, in part because of Josefowicz's greater timbral edginess. Those who prefer a tonally more sumptuous reading, richer may prefer Bednarz's version by about the same measure as those who lean to the eerily expressive may prefer Josefowicz's.

With its clear recorded sound and its revelatory thoughtful performances, the duo's release deserves a warm recommendation--especially, perhaps, for their ingratiating performance of Szymanowski's sonata.

Robert Maxham, Fanfare